Project managers or the organization can divide projects into phases to provide better management control with appropriate links to the ongoing operations of the performing organization. Collectively, these phases are known as the project life cycle. Many organizations identify a specific set of life cycles for use on all of their projects.

The project life cycle defines the phases that connect the beginning of a project to its end. For example, when an organization identifies an opportunity to which it would like to respond, it will often authorize a feasibility study to decide whether it should undertake the project. The project life cycle definition can help the project manager clarify whether to treat the feasibility study as the first project phase or as a separate, stand-alone project. Where the outcome of such a preliminary effort is not clearly identifiable, it is best to treat such efforts as a separate project. The phases of a project life cycle are not the same as the Project Management Process Groups described in detail in Chapter 3.

The transition from one phase to another within a project’s life cycle generally involves, and is usually defined by, some form of technical transfer or handoff. Deliverables from one phase are usually reviewed for completeness and accuracy and approved before work starts on the next phase. However, it is not uncommon for a phase to begin prior to the approval of the previous phase’s deliverables, when the risks involved are deemed acceptable. This practice of overlapping phases, normally done in sequence, is an example of the application of the schedule compression technique called fast tracking.

There is no single best way to define an ideal project life cycle. Some organizations have established policies that standardize all projects with a single life cycle, while others allow the project management team to choose the most appropriate life cycle for the team’s project. Further, industry common practices will often lead to the use of a preferred life cycle within that industry.

Project life cycles generally define:

What technical work to do in each phase (for example, in which phase should the architect’s work be performed?)

When the deliverables are to be generated in each phase and how each deliverable is reviewed, verified, and validated

Who is involved in each phase (for example, concurrent engineering requires that the implementers be involved with requirements and design)

How to control and approve each phase.

Project life cycle descriptions can be very general or very detailed. Highly detailed descriptions of life cycles can include forms, charts, and checklists to provide structure and control.

Most project life cycles share a number of common characteristics:

Phases are generally sequential and are usually defined by some form of technical information transfer or technical component handoff.

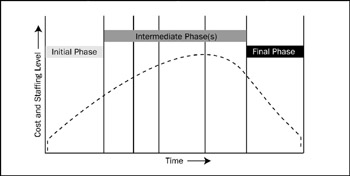

Cost and staffing levels are low at the start, peak during the intermediate phases, and drop rapidly as the project draws to a conclusion. Figure 2-1 illustrates this pattern.

Figure 2-1. Typical Project Cost and Staffing Level Across the Project Life Cycle

The level of uncertainty is highest and, hence, risk of failing to achieve the objectives is greatest at the start of the project. The certainty of completion generally gets progressively better as the project continues.

The ability of the stakeholders to influence the final characteristics of the project’s product and the final cost of the project is highest at the start, and gets progressively lower as the project continues. A major contributor to this phenomenon is that the cost of changes and correcting errors generally increases as the project continues.

Although many project life cycles have similar phase names with similar deliverables, few life cycles are identical. Some can have four or five phases, but others may have nine or more. Single application areas are known to have significant variations. One organization’s software development life cycle can have a single design phase, while another can have separate phases for architectural and detailed design. Subprojects can also have distinct project life cycles. For example, an architectural firm hired to design a new office building is first involved in the owner’s definition phase while doing the design, and in the owner’s implementation phase while supporting the construction effort. The architect’s design project, however, will have its own series of phases from conceptual development, through definition and implementation, to closure. The architect can even treat designing the facility and supporting the construction as separate projects, each with its own set of phases.

The completion and approval of one or more deliverables characterizes a project phase. A deliverable is a measurable, verifiable work product such as a specification, feasibility study report, detailed design document, or working prototype. Some deliverables can correspond to the project management process, whereas others are the end products or components of the end products for which the project was conceived. The deliverables, and hence the phases, are part of a generally sequential process designed to ensure proper control of the project and to attain the desired product or service, which is the objective of the project.

In any specific project, for reasons of size, complexity, level of risk, and cash flow constraints, phases can be further subdivided into subphases. Each subphase is aligned with one or more specific deliverables for monitoring and control. The majority of these subphase deliverables are related to the primary phase deliverable, and the phases typically take their names from these phase deliverables: requirements, design, build, test, startup, turnover, and others, as appropriate.

A project phase is generally concluded with a review of the work accomplished and the deliverables to determine acceptance, whether extra work is still required, or whether the phase should be considered closed. A management review is often held to reach a decision to start the activities of the next phase without closing the current phase, for example, when the project manager chooses fast tracking as the course of action. Another example is when an information technology company chooses an iterative life cycle where more than one phase of the project might progress simultaneously. Requirements for a module can be gathered and analyzed before the module is designed and constructed. While analysis of a module is being done, the requirements gathering for another module could also start in parallel.

Similarly, a phase can be closed without the decision to initiate any other phases. For example, the project is completed or the risk is deemed too great for the project to be allowed to continue.

Formal phase completion does not include authorizing the subsequent phase. For effective control, each phase is formally initiated to produce a phase-dependent output of the Initiating Process Group, specifying what is allowed and expected for that phase, as shown in Figure 2-3. A phase-end review can be held with the explicit goals of obtaining authorization to close the current phase and to initiate the subsequent one. Sometimes both authorizations can be gained at one review. Phase-end reviews are also called phase exits, phase gates, or kill points.

Many projects are linked to the ongoing work of the performing organization. Some organizations formally approve projects only after completion of a feasibility study, a preliminary plan, or some other equivalent form of analysis; in these cases, the preliminary planning or analysis takes the form of a separate project. For example, additional phases could come from developing and testing a prototype prior to initiating the project for the development of the final product. Some types of projects, especially internal service or new product development projects, can be initiated informally for a limited amount of time to secure formal approval for additional phases or activities.

The driving forces that create the stimuli for a project are typically referred to as problems, opportunities, or business requirements. The effect of these pressures is that management generally must prioritize this request with respect to the needs and resource demands of other potential projects.

The project life cycle definition will also identify which transitional actions at the end of the project are included or not included, in order to link the project to the ongoing operations of the performing organization. Examples would be when a new product is released to manufacturing, or a new software program is turned over to marketing. Care should be taken to distinguish the project life cycle from the product life cycle. For example, a project undertaken to bring a new desktop computer to market is only one aspect of the product life cycle. Figure 2-4 illustrates the product life cycle starting with the business plan, through idea, to product, ongoing operations and product divestment. The project life cycle goes through a series of phases to create the product. Additional projects can include a performance upgrade to the product. In some application areas, such as new product development or software development, organizations consider the project life cycle as part of the product life cycle.